Comparing GPT-4, 3.5, and some offline local LLMs at the task of generating flashcards for spaced repetition (e.g., Anki)

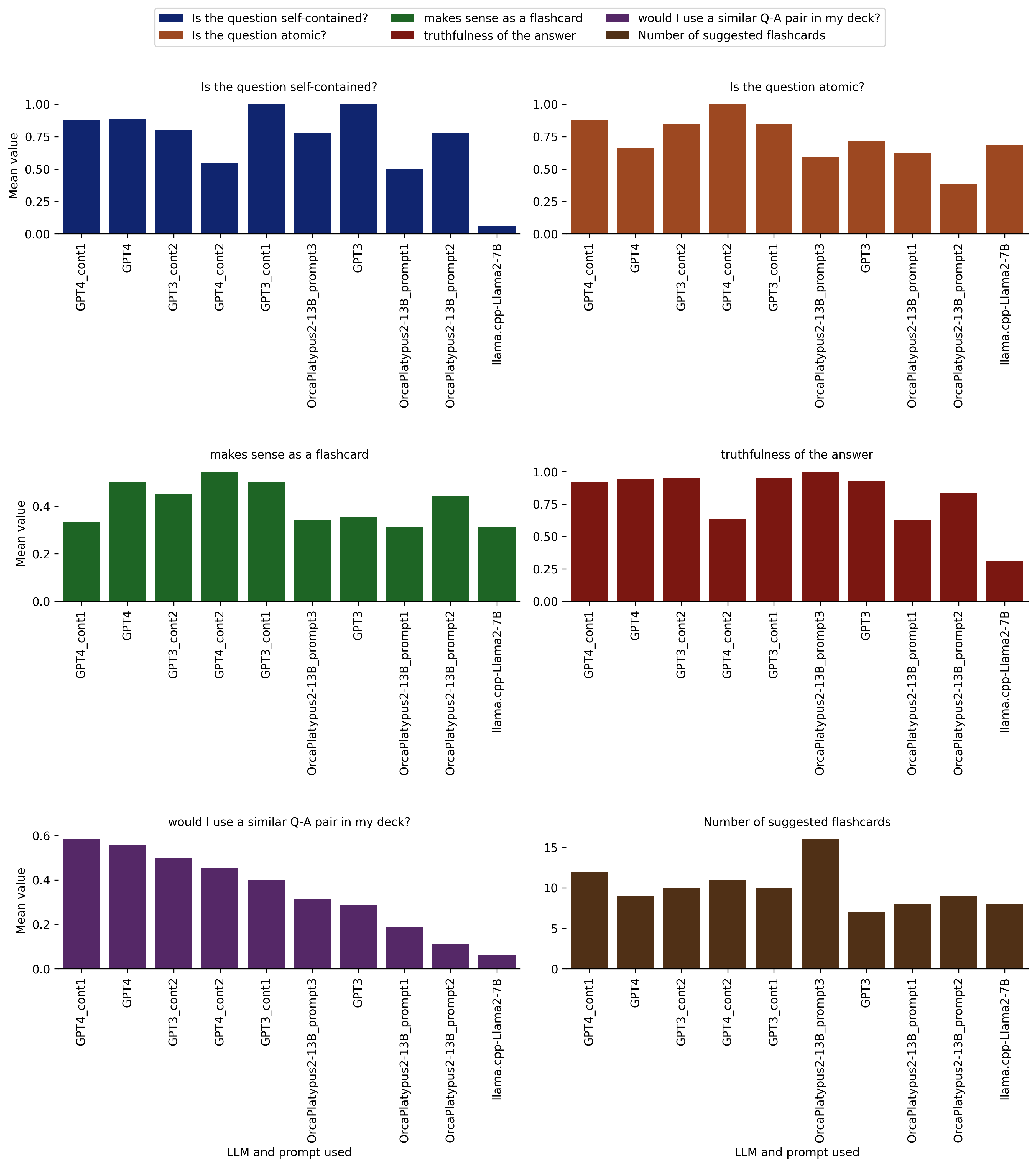

tldr: I used GPT-4 Turbo, GPT-3.5 Turbo, and two open-source offline LLMs to create flashcards for a spaced repetition system (Anki) on a mathematical topic; I rated the 100 LLM-suggested flashcards (i.e., question-answer pairs) along the dimensions of truthfulness, self-containment, atomicity, whether the question-answer makes sense as a flashcard, and whether I would include a similar flashcard in my deck; I analyzed and compared the different LLMs’ performance based on all of that; then crowned the winner LLM ![]() or maybe not… And, because the blog post ended up being long and detailed, here is a figure combining all of the final results:

or maybe not… And, because the blog post ended up being long and detailed, here is a figure combining all of the final results:

Figure caption: Models/prompts and their mean ratings along multiple rating dimensions, assigned by me in a (to the extent possible) blinded fashion. The models/prompts are sorted by “would I use a similar Q-A pair in my deck?”, which for my purposes is the main quality indicator for the generated flashcards.

Figure caption: Models/prompts and their mean ratings along multiple rating dimensions, assigned by me in a (to the extent possible) blinded fashion. The models/prompts are sorted by “would I use a similar Q-A pair in my deck?”, which for my purposes is the main quality indicator for the generated flashcards.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Note on the open-source models used: I ran the experiments described below at the end of November 2023 using a single GPU and models available at that time. Given the pace at which LLMs develop, you should probably take the results with a grain of salt. Moreover, the locally run open-source models that I used may not have been the very best even at that time (even considering my hardware constraints).

![]()

![]()

![]()

Introduction

Recently in my reading I came across the statistical metric Fleiss’ kappa, which I had seen before, but no longer could remember the definition of. This is exactly the type scenario, where I would like to include at least the definition of this statistical assessment measure into my spaced repetition database (Anki) – or, in other words, “ankify” the concept.

I learned about spaced repetition and Anki about 6 years ago from several blog posts by Michael Nielsen, who specifically also covers the topic of creating flashcards for sophisticated mathematical topics (Nielsen, 2018; Nielsen, 2019). Indeed I have noticed beneficial effects of my use of Anki as a knowledge worker over the last 5-6 years as well as for some of my hobbies. I just wish sometimes that I were more consistent and disciplined in my use of Anki. But let’s reserve this discussion for another occasion, since the benefits and challenges of spaced repetition is not the topic of this blog post.

I have also been playing around with LLMs for a little while. But the vast majority of it was using the OpenAI API (mostly via the excellent ShellGPT and sometimes from Python directly), and I was looking for a good excuse to play around with LLMs more and to try out some open-source models that can run locally on my computer, such as those based on Llama 2 (unfortunately the Mixtral models were not released yet at the time). So, it seemed it would be a great idea to use different LLMs to generate a bunch of suggested Anki flashcards based on articles about Fleiss’ kappa, and I based my prompts to the LLMs in part on Michael Nielsen’s articles referenced above (see below for details about my prompting strategies).

As the primary goal of this exercise, I wanted to compare the outputs from different LLMs in a systematic way on this task of my personal interest, as I had no idea how open-source LLMs that I run on my local computer would stake up against something like ChatGPT.

Overview

For the main part of this blog post, I will go through the models/LLMs and prompts first, and then describe the analysis and the results. So, overall this is what we are doing here:

-

AI-based flashcard generation

I used GPT-4 Turbo and GPT-3.5 Turbo via the OpenAI API, and two open-source LLMs running on my local computer (after trying several others), in combination with several prompting strategies – in total 10 different LLM-prompt combinations – to generate 100 Anki cards (question-answer pairs).1

-

LLM/prompt performance analysis “study”

There are the following components to this “study”:

- 2.1 I rate the outputs from the different LLMs along several rating categories (which I came up with for this task), blinding myself to the extent possible with respect to which LLM was used for which output.

- 2.2 I use OpenAI’s text embeddings to measure the relatedness between the LLM-generated flashcards and flashcards that I ultimately included into my Anki deck.

- 2.3 Finally I visualize and analyze the results from points 2.1 and 2.2.

There may be many imperfections in the performance “study” and it could be considered simplistic, but luckily we aren’t looking at a peer-reviewed scientific publication here but rather just a blog post that I’m quickly writing on a Sunday afternoon ([Narrator’s voice]: Well, it actually took much more than that one Sunday afternoon, with several intense writing sessions and extended breaks in between).

Models and prompts

An excellent overview on how to use the OpenAI API and how to deploy local LLM models on your own hardware is provided in a Youtube video lecture by Jeremy Howard, and a substantial portion of the code that was used for this blog post originates from that video: A Hackers’ Guide to Large Language Models

In this section, I will go through each model and each prompt that I used, as well as my rationale behind it.

GPT-4

For my first attempt I used the GPT-4 Turbo model (gpt-4-1106-preview), which had been released shortly before I started these experiments.

Initial prompt (GPT4 in the results figure)

My initial prompt for the tasks of interest here was:

prompt = "Create flashcards for a spaced repetition system on the topic of Fleiss' Kappa for me based on the wikipedia articles that I include below (after the string '--- Wikipedia articles ---'). You should mostly ignore your previous knowledge about Fleiss' Kappa and rely on the information provided in the Wikipedia articles below."

which was followed in the Python code by:

prompt = prompt + "\n\n--- Wikipedia articles ---\n\n"

prompt = prompt + "\n\n" + wiki_fleiss_kappa

prompt = prompt + "\n\n" + wiki_cohens_kappa

prompt = prompt + "\n\n" + wiki_scotts_pi

where wiki_fleiss_kappa, wiki_cohens_kappa, and wiki_scotts_pi are copies of the respective Wikipedia articles (Wikipedia, 2023; Wikipedia, 2023; Wikipedia, 2023), which I scraped within my Python code using the Wikipedia-API package.

The GPT-4 Turbo model with this prompt returned 9 flashcards, which generally were pretty decent, such as:

(…)

Flashcard 3: Applicability of Fleiss’ Kappa

- Front: Can Fleiss’ Kappa be used with various types of data?

- Back: Yes, Fleiss’ Kappa can be used with binary, nominal, or ordinal data, but for ordinal data, statistics that account for ordering, like Kendall’s coefficients, are usually more appropriate.

Flashcard 4: Formula for Fleiss’ Kappa

- Front: What is the formula for calculating Fleiss’ Kappa?

- Back: κ = (P̄ - P̄e) / (1 - P̄e), where P̄ is the mean of the extent to which raters agree for each subject, and P̄e is the mean of the proportion of all assignments which were to each category by chance.

(…)

However, I wanted to get the model to generate more sophisticated question-answer pairs that would tease out more of the mathematical subtleties on the topic and quiz me for a deeper understanding of the concepts.

A longer more complex prompt (GPT4_cont1 in the results figure)

To “teach” the model how I want it to go about creating Anki cards for me and about the purpose of the Anki cards (what I want to get out of my spaced repetition practice), I decided to first feed it with two articles on the topic (Nielsen, 2018; Nielsen, 2019):

prompt = "I want to you to learn about spaced repetition systems (SRS) such as Anki, so that you can act as a professional Anki card creator, with a particular expertise at creating Anki cards for topics in mathematics and statistics. Below I provide you first with an introductory text about spaced repetition systems by Michael Nielsen (starting after the string '--- FIRST TEXT ---' and ending with the string '--- FIRST TEXT END ---'). Then I provide you with another article by Michael Nielsen about creating Anki cards for mathematical topics (starting after the string '--- SECOND TEXT ---' and ending with the string '--- SECOND TEXT END ---'). Based on this reading material please explain what process you will follow, as a professional Anki card creator, to create Anki cards for me based on other articles, papers or notes that I will provide in the future."

which was followed by:

prompt = prompt + '\n\n--- FIRST TEXT ---\n\n' + text_srs

prompt = prompt + '\n\n--- FIRST TEXT END ---\n\n'

prompt = prompt + '\n\n--- SECOND TEXT ---\n\n' + text_srs_math

prompt = prompt + '\n\n--- SECOND TEXT END ---\n\n'

where text_srs and text_srs_math are plain text versions of (Nielsen, 2018; Nielsen, 2019), downloaded from within my Python code with the Beautiful Soup library.

After the model had output an explanation of the Anki card generation process based on this prompt, I followed up the conversation with the actual request to create Anki flashcards for me:

prompt2 = "Create Anki cards on the topic of Fleiss' Kappa for me based on the wikipedia articles that I include below (after the string '--- Wikipedia articles ---'). You should mostly ignore your previous knowledge about Fleiss' Kappa and rely on the information provided in the Wikipedia articles below."

where again I appended the prompt with the three articles (Wikipedia, 2023; Wikipedia, 2023; Wikipedia, 2023).

This approach provided 12 AI-suggested flashcards, which indeed seemed to go more in the direction where I wanted them to go. Here are a couple of examples of cards I like from this output:

Calculation of Agreement Proportions

Q: How do you calculate the proportion of assignments to the j-th category (pj) in Fleiss’ kappa? A: pj = (1 / Nn) ∑ from i=1 to N nij, with N being the total number of subjects, n the number of ratings per subject, and nij the number of raters who assigned the i-th subject to the j-th category.

Q: Define Pi in the context of Fleiss’ kappa. A: Pi is the extent to which raters agree for the i-th subject, calculated as (1 / n(n-1)) * ∑ from j=1 to k nij(nij-1).

Further continuing the same conversation with GPT-4-Turbo (GPT4_cont2 in the results figure)

Trying to get even more useful (to me) Anki cards, I continued the same chat with the following prompt:

prompt3 = "Please create additional cards for deeper mathematical understanding, including more detailed breakdown of the mathematical definitions and formulas, the influence of different numbers of categories on kappa values, and comparisons with related statistics such as Scott's Pi and Cohen's kappa."

This gave 11 additional suggested question-answer pairs. Some were rephrased repeats of the last output, some were new and interesting, but generally I felt that GPT-4 was getting to its limits on the task here, likely because the Wikipedia articles I fed it simply didn’t provide enough content to go into more depth on the topic.

GPT-3.5 Turbo

Having the GPT-4 Turbo output, an important question is whether GPT-3.5 Turbo can perform just as well, given that, compared to GPT-4, it is cheaper or even free to use. From my Python code I used the “gpt-3.5-turbo-1106” model through the OpenAI API. I initially had tried the “gpt-3.5-turbo” model, but it couldn’t handle the context lengths of my prompt, which was the same as my “Initial prompt” for GPT-4 described above.

Initial prompt (GPT3 in the results figure)

I started with the same prompt as the “initial prompt” for GPT-4 described above.

A longer more complex prompt (GPT3_cont1 in the results figure)

For the “longer more complex prompt” (described in detail in the GPT-4 section above), the model couldn’t handle both supplied articles, (Nielsen, 2018; Nielsen, 2019), due to context length limitations. So, I only fed it one of the two articles, (Nielsen, 2019), leaving the rest of the prompt unchanged.

Further continuing the same conversation with GPT-3.5-Turbo (GPT3_cont2 in the results figure)

The prompt here was identical to the one used in the respective GPT-4 section above.

Local/offline open-source LLMs

Next I wanted to try out a few open-source models, running locally on my computer, to perform the same flashcard generation task.

There is an overwhelming number of options for open-source models that can be downloaded from Huggingface (or maybe one should rather call them “open-weight models” for a better more precise terminology). So, a lot to choose from, and there are multiple leaderboards that can guide the choice, such as the Huggingface “Open LLM Leaderboard” or the “Chatbot Arena”. However, I haven’t dedicated time yet to thoroughly understand the metrics and construction of such leaderboards. For that reason, I didn’t guide my model choices on any leaderboards for now. What I did instead was try out a few different models that I’ve seen mentioned on the internet in other people’s experimentations. I’ve then chosen to stick with a couple of those models that would run on my hardware given the prompts I was using, and seemed to provide useable output for the task in question. The computer I was using for this is basically a gaming PC with an Nvidia RTX 4090 graphics card and, other than that, somewhat older mid-level components.

Note that I ran the experiments described below at the end of November 2023. The available open-source models/solutions may have improved considerably since then, or may not have been the very best open models for the given task in the first place (even for my hardware constraints). I would appreciate any hints about superior open models for the task that can run offline on my local machine (for instance on a single Nvidia RTX 4090 or a comparable gaming GPU, or possibly CPU-only but I’m impatient).

Running open LLMs on a modern Nvidia GPU

Running an LLM on your own Nvidia GPU is made relatively easy by the Huggingface’s Transformers library in conjunction with PyTorch.

The open-source models that I tried initially (various derivatives of the Llama 2 LLM) tended to run out of GPU memory, given the prompts I was using (recall that I need to pass in at least most of the Wikipedia article on Fleiss’ Kappa as part of the prompt (Wikipedia, 2023)), although I had shortened the prompts considerably compared to what I used for GPT-4 and GPT-3.5 above. So, I had to leverage derivatives of popular LLMs that are more memory-efficient through the use of quantization techniques. Specifically, for the results presented below, I ended up using the model TheBloke/OpenOrca-Platypus2-13B-GPTQ, which is a GPTQ quantized version of OpenOrca-Platypus2-13B, which in turn is a merge of two fine-tuned models based on LLaMA2-13B by Meta. The reason I chose that specific model for the experiments is partly due to it being one of the models used by Jeremy Howard in the video referenced above (if I recall correctly), and also based on the initial experimentation with multiple other models.

Adapting the previous prompts for LLMs running on my local PC (OrcaPlatypus2-13B_prompt1 in the results figures below)

Due to context length limitations, I used the following shorter prompt (compared to the GPT prompts above):

Spaced repetition is an evidence-based learning technique that is usually performed with flashcards, which are essentially question-answer pairs. Newly introduced and more difficult flashcards are shown more frequently, while older and less difficult flashcards are shown less frequently in order to exploit the psychological spacing effect. The use of spaced repetition has been proven to increase the rate of learning.

Given the text below (after the string 'TEXT'), suggest flashcards (i.e. questions and the corresponding answers) for a spaced repetition system, in order to help an undergraduate student to learn the presented information. Please provide your suggested flashcards as question-answer pairs (Q: ..., A: ...).

\n\n

TEXT.

where only the Wikipedia article on Fleiss’ kappa (Wikipedia, 2023) was appended to the prompt, but unlike previously, not the articles on Cohen’s Kappa and Scott’s Pi (Wikipedia, 2023; Wikipedia, 2023):

prompt = prompt + "\n\n" + wiki_fleiss_kappa

Then I converted this prompt into the instruction-response template format of base Platypus2. By “template format” I mean a standardized prompt formatting that can look something like, ### Instruction: ... ### Response:, or User: ... <|end_of_turn|>Assistant:, etc., which is needed for the open-source LLMs (not sure if all of them though) to ensure that they provide an actual response to my query rather than take it as a piece of text to be extended in arbitrary manner with some additional text.

To be honest, I’m not quite sure which prompt template format would have been best to use, but this seemed to work well enough.

This query gave me 7 reasonably-looking flashcards as question-answer pairs. After that the output started deteriorating, giving a flashcard that was grammatically mostly correct but didn’t make any sense, and then to disconnected sentence fragments, and finally to a repeated sequence of characters. Parts of the example output is provided in the following for illustration:

1. Question: What is the most suitable measure for assessing agreement between a fixed number of raters when assigning categorical ratings to a number of items or classifying items?

Answer: Fleiss’ kappa.

2. Question: When should we use Cohen’s kappa over Fleiss’ kappa?

Answer: Fleiss’ kappa works for any number of raters, while Cohen’s kappa only works when assessing the agreement between two raters or the intra-rater reliability.

(…)

[Five other reasonable flashcards (not shown)]

[Then the output starts to deteriorate:]

8. Question: If the sum of all cells is equal to 1440, what does it mean?

Answer: If the sum of all cells equals 40 to 40 cells, then it would mean that this value is used to maintain the consist of data40. The rater and Cells and classified data’s.

9. In this manner, but the consistent with the Pearson and consistent with Pearson and in terms of the analysis and classified data within correlation and the agreement, data. The data.

9.5. Pearson and the data. The Pearson and the agreement4. Each rater and correlation and in the agreement with the data.5. The data. correlation analysis, with6. Each raters and data.5.5. The data on the ratio and correlation and the data. Each entry rate. The data. Each rater and correlation and data.

9. The data.1. The agreement and the data; that helps in6. The data.5. Each pair of data.4.0. The data. Analysis in terms5.02. Each. the data. The data.5.

6. The more. Each.6. The data.7.11. the data.5.7.5.5.0.6.5.5. the6.6.5.5.5.6.6.5.data.5.6.5.5.5.6.6.6.6.6.5.6.5.6.6.6.5.5.6.6.6.6.5.6.5.5.6.6.5.6.5.6.6.6. .5.6.6,6.5.6.5.5.5.6.5.6.5.5.6.5.5.5.5.6.5.5.5.6.5. 6.5.5.5. 5.5.5.5.5.5.5.5. 5.6.6. 6 to 5.5.5.5. 5.5.6. 6.5.5.

Additional attempt with more manual prompt curation (OrcaPlatypus2-13B_prompt2 in the results figures below)

After the partially successful attempt above, I decided to try replacing the scraped Wikipedia article on Fleiss’ Kappa with a somewhat more manually curated text about Fleiss’ Kappa. That “more manually curated text” was me copy-pasting only the relevant parts of the Wikipedia article, and with a better formatting than what I had obtained previously with the Wikipedia API Python package in an automated fashion.

In addition, the copy-pasted Wikipedia excerpts were prepended by a very simple sentence describing the task:

Given the text below, suggest questions and the corresponding answers to use in a quiz or exam for a class of undergraduate students.

In my experience, using that simple description of the task, which doesn’t even mention “spaced repetition” or “flashcards”, helped to improve the output for some other locally run LLMs that I tried (not shown) – predominantly smaller models, which otherwise tended to not address the right task (for example, suggesting questions about the spaced repetition concept rather than the desired topic) or to produce many hallucinations.

The result of this indeed seemed better compared to the last prompt, and also didn’t exhibit artifacts like the ones illustrated in the last subsection. However, from a practical perspective the value of that practice is a little questionable, because, if I can take the time to curate a better input text for the LLM manually, I could as well just have used that same time to create Anki flashcards manually without using the LLM.

Second variation of the “more manually curated prompt” (OrcaPlatypus2-13B_prompt3 in the results figures below)

For the OpenOrca-Platypus2-13B model I have also made a variation of the same prompt, referred to as OrcaPlatypus2-13B_prompt3, where the flashcard generation task for spaced repetition was described in somewhat more detail:

Spaced repetition is an evidence-based learning technique that is usually performed with flashcards, which are essentially question-answer pairs. Newly introduced and more difficult flashcards are shown more frequently, while older and less difficult flashcards are shown less frequently in order to exploit the psychological spacing effect. The use of spaced repetition has been proven to increase the rate of learning.

Given the text below (after the string 'TEXT'), suggest flashcards (i.e. questions and the corresponding answers) for a spaced repetition system, in order to help an undergraduate student to learn the presented information.

\n\n

TEXT

where the “more curated” text on Fleiss’ Kappa was appended after “TEXT”.

LLMs using llama.cpp on the CPU (llama.cpp-Llama2-7B in the results figures)

Finally, I also wanted to explore the use of LLMs without an Nvidia GPU, i.e., running on the CPU of my computer, by utilizing the llama.cpp Python package. While llama.cpp allows you to run Meta’s LLaMA models on different kinds of hardware, I used the default Linux install which runs on CPU only.

The specific model I used in conjunction with llama.cpp was llama-2-7b-chat.Q5_K_M.gguf (again, something I saw in Jeremy Howard’s “A Hackers’ Guide to Large Language Models” video if I remember correctly).

It was difficult to experiment with prompts for llama.cpp, because, when using CPU only, text generation is slow. So, in the following, I analyze results only for a single prompt:

Spaced repetition is an evidence-based learning technique that is usually performed with flashcards, which are essentially question-answer pairs. Newly introduced and more difficult flashcards are shown more frequently, while older and less difficult flashcards are shown less frequently in order to exploit the psychological spacing effect. The use of spaced repetition has been proven to increase the rate of learning.

Given the text below (after the string 'TEXT'), suggest flashcards (i.e. questions and the corresponding answers) for a spaced repetition system, in order to help an undergraduate student to learn the presented information. Please provide your suggested flashcards as question-answer pairs (Q: ..., A: ...).

\n\n

TEXT

where as before the Wikipedia article about Fleiss’ Kappa was appended to the prompt, and no additional information was appended due to context length limitations.

The output contained 8 nicely formatted suggested flashcards, without anything completely nonsensical or hallucinated.

Performance evaluation of LLMs via a “study” with a single human rater (myself)

To remind you, as discussed at the top of this post, there are the following main components to this performance evaluation “study”:

- I rate the outputs from the different LLMs along several rating categories (which I came up with for this task), blinding myself to the extent possible with respect to which LLM was used for which output.

- I use OpenAI’s text embeddings to measure the relatedness between the LLM-generated flashcards and flashcards that I ultimately included into my Anki deck.

- Finally I visualize and analyze the results from items 1 and 2.

As mentioned in the introduction, there could be many imperfections and limitations in this assessment “study” of LLM performance, but we aren’t going to worry about that, since this is just a random experiment I’m doing in my spare time.

Rating the outputs of the LLMs by a human (me)

After creating the LLM-generated flashcards, I put them in random order into a spreadsheet which also excluded any indication with respect to the models or promtps used for each output. Then I put this project aside for a week, which allowed me to mostly forget what question-answer pair was suggested by which LLM/prompt. This one week break can be viewed as slightly analogous to a wash-out period (albeit a very short one) in reader studies for performance evaluation in diagnostic medicine, as I was taking a deliberate extended break with the goal of forgetting what I knew about the data. When I came back to this project, I rated each AI-suggested flashcard along the following five dimensions:

- Is the LLM-proposed question self-contained?

- Is the LLM-proposed question atomic?

- Does the LLM-proposed question-answer pair make sense as a flashcard? This could be a somewhat subjective category, accounting for such factors as whether the flashcard is relevant to the topic, sophisticated enough, not too obvious but not too hard either, etc.

- Truthfulness of the LLM-proposed flashcard, i.e., whether the proposed answer is actually a correct answer to the proposed question.

- Would I likely use this flashcard (or a very similar flashcard)? i.e., would I use this Q-A pair (or a very similar one) in my Anki deck?

As mentioned above, I blinded myself to the models/prompts used for each generation, and leveraged my forgetfulness by taking a one week break between generating the flashcards and rating them. Within each category I put ratings on a scale 0, 0.5, 1. That means I sometimes gave partial credit. For example, for truthfulness, an AI-suggested answer to a flashcard could have two parts, where one may be correct while the other false; such a two-part answer flashcard would likely get a 0.5 in the “truthfulness” category and a 0 for “atomicity”.

Finally, I created flashcards for my actual Anki deck using 21 of the suggested Q-A pairs as basis for my final Anki cards (only one of the final cards matches a suggested card exactly).

Calculating embeddings

In addition, I looked at embeddings of each AI-generated flashcard, and compared how closely they match the embeddings of the 21 Anki cards that I actually ended up including in my deck (manually modified flashcards based on some of the AI-generated ones).

For this I used OpenAI’s embedding model text-embedding-ada-002.

I used cosine similarity, a metric similar to the widely-known Pearson’s correlation coefficient, to compare the text embedding of each of the 100 AI-generated card with each of my 21 human-curated flashcards. I then recorded the maximum value from the 21 cosine similarity values for each AI-generated flashcard, which I denote as max_cos_sim. The max_cos_sim values can be used as another approach to compare the generative models in this experiment, attempting to evaluate how similar the output of each model is to the flashcards that I eventually deemed worthy of including in my spaced repetition deck.

Analysis methods

I simply compared the means per model/prompt. No sophisticated statistical analysis was performed at this time, because of my time limits for this blog post and complications due to the small sample sizes and various sources of potential bias or variability that would need to be accounted for. More detail on the analysis of each specific rating categorization as well as the embeddings is provided in the subsections under “Results” below.

If I have time and interest in the future, I may update the analysis with:

- Error bars in the bar graphs to report the standard errors around the estimated mean values.

- An estimate for intra-rater agreement for my ratings in the different categories.

Results and discussion

Comparison of embeddings

The mean and standard deviation values of the max_cos_sim metric (described in the section “Calculating embeddings” above) provide numerical measures of how similar the AI-generated flashcards are to the ones I ultimately added to my Anki deck. However, I found that this is a poor way of comparing LLMs on this task, for the reasons outlined below. The breakdown per model/prompt is as follows:

| model/prompt |

max_cos_sim: mean (std. dev.) |

| GPT4 | 0.964849 (0.037430) |

| GPT3 | 0.957126 (0.031817) |

| GPT3_cont1 | 0.956216 (0.033335) |

| GPT4_cont1 | 0.953869 (0.037121) |

| GPT3_cont2 | 0.951629 (0.046560) |

| GPT4_cont2 | 0.942788 (0.033649) |

| OrcaPlatypus2-13B_prompt2 | 0.938141 (0.044916) |

| OrcaPlatypus2-13B_prompt3 | 0.931788 (0.047142) |

| OrcaPlatypus2-13B_prompt1 | 0.905019 (0.053023) |

| llama.cpp-Llama2-7B | 0.891498 (0.030630) |

The GPT models are in front according to this metric. But note that this does not account for factors such as diversity of the generated flashcards, how sophisticated they are, different numbers of cards generated by each model, etc.

Generally, the max_cos_sim metric turned out to not be very informative for reasons including:

- All values are similarly large without statistically significant separation.

- The highest scoring models may not necessarily provide the highest quality flashcards, but may just be correlated to a small set of particularly easy-to-come-up-with question-answer pairs in my final deck.

- For some of the models/prompts, where the mean is relatively lower, the standard deviation is higher, indicating that perhaps they yielded some lower quality flashcards but also perhaps some high-quality ones, which could be unique to that model and therefore particularly useful.

An appropriately designed custom metric could be used instead of the max_cos_sim metric proposed above to account for some of these issues. For instance, some problems with max_cos_sim stem from it evaluating a given model’s generated flashcards as independent samples, when in fact the task is to come up with an optimal set of flashcards to study a given topic (i.e., it must have sufficient coverage of the topic, the desired amount of breadth and depth, avoid repetition, etc.). Therefore, an appropriate specialized performance metric would likely have to be constructed in such a way, so that it compares the entire set of each model’s generated cards (i.e., considering it as a whole rather than as independent cards) against the entire set of the flashcards that were ultimately included in my deck (again, encompassing everything at once).

However, not wanting to spend even more time on this project, I didn’t investigate these aspects further.

Another drawback of comparing text embeddings that I want to highlight is that subtle word changes can make a huge change in the overall quality of a flashcard while the embeddings will stay very similar. By changing a word to another word that has a related but somewhat different meaning, a flashcard can turn from something providing a lot of insight to something that’s unclear or even false. For example compare the following question that was generated by GPT-3.5 Turbo in this experiment:

Why may Fleiss’ kappa not be suited for cases where all raters rate all items?

with the sightly modified question:

Why is Fleiss’ kappa not suited for cases where all raters rate all items?

The small change of the verb from “may be” to “is” makes a big difference for the scientific meaning of the sentence, but the similarity between embeddings is very high with a cosine similarity of 0.9925.

That is not to say that the similarity between embeddings makes no sense at all – I in fact do observe that the specific question-answer pairs, which were actually used as the basis for my Anki cards, have generally higher max_cos_sim values than those questions which I didn’t end up using, as shown in this table:

max_cos_sim |

mean (std. dev.) | median |

| Q-A pairs I used | 0.984527 (0.026339) | 0.995037 |

| Q-A pairs I didn’t use | 0.928203 (0.040223) | 0.938435 |

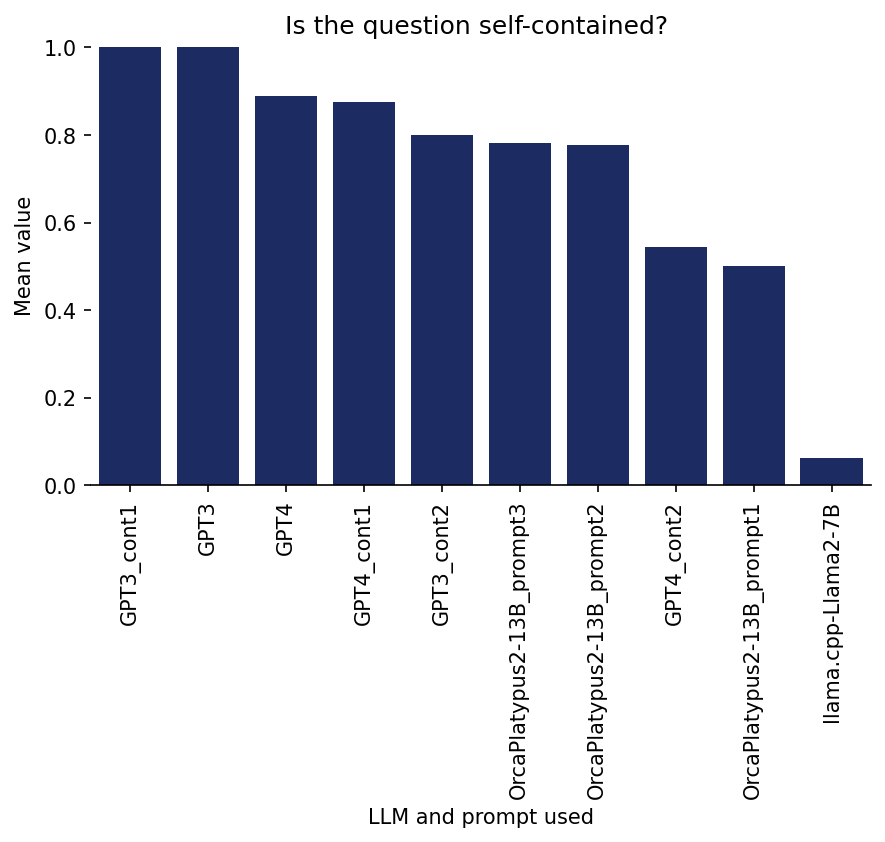

Ratings on 1. Self-containment

Is the question self-contained?

Here, I was rating whether the question can be understood without any additional explanations (such as definitions), beyond some kind of common knowledge (of course, there is some room for interpretation of what I consider not needing a definition).

Here is an example of a question from the GPT4_cont2 output which I rated as not self-contained:

Describe how to compute ( P_i ) for subject ( i ).

Here is a bar graph of the results per model/prompt:

The most striking observation here is that Llama.cpp received very low scores with a large separation from the other models. But note that this is a bit unfair towards llama.cpp, because llama.cpp generated flashcards under headings/topics describing the context to a certain extent (for example: “Topic 1: Classification agreement between raters (P i )”), but when I rated the generated cards, I only included the questions and answers (without any such headings), in order to blind myself to the models/prompts by having the same format for all of them.

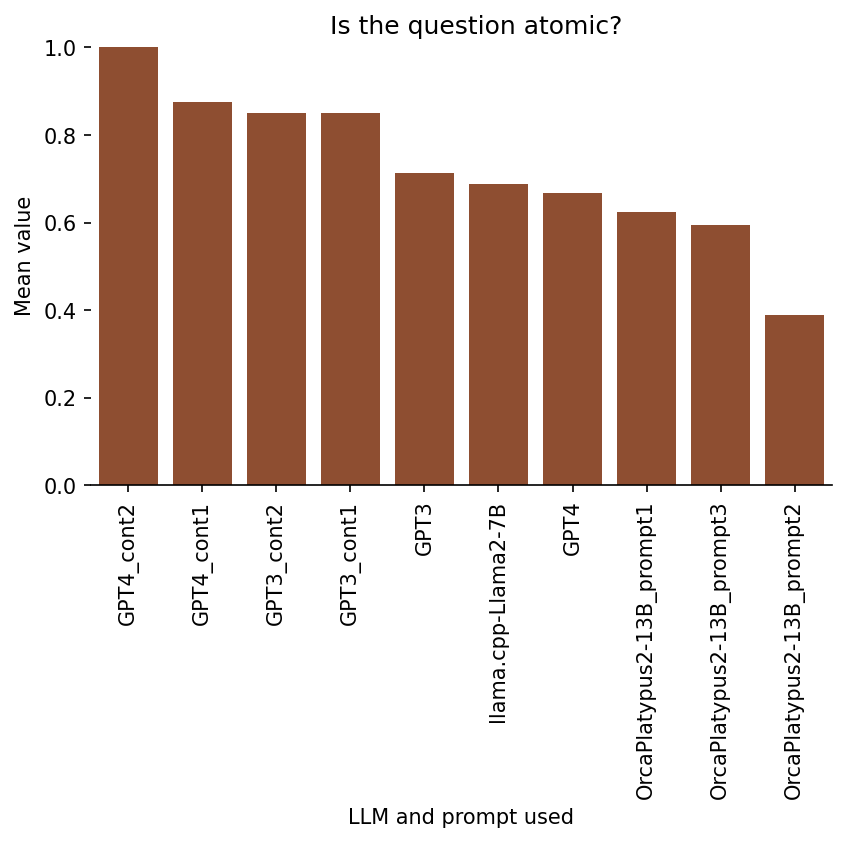

Ratings on 2. Atomicity

Is the question atomic?

For this category, I was rating, essentially, whether a given flashcard is testing for recall of a single concept. That is, a two-part answer would likely not be atomic.

Here is an example of a question suggested by llama.cpp-Llama2-7B that I rated as not “atomic”, because it is asking to list “some” disadvantages of Kappa, rather than asking about one specific disadvantage:

What are some disadvantages of Kappa?

Here is the breakdown of results per model/prompt:

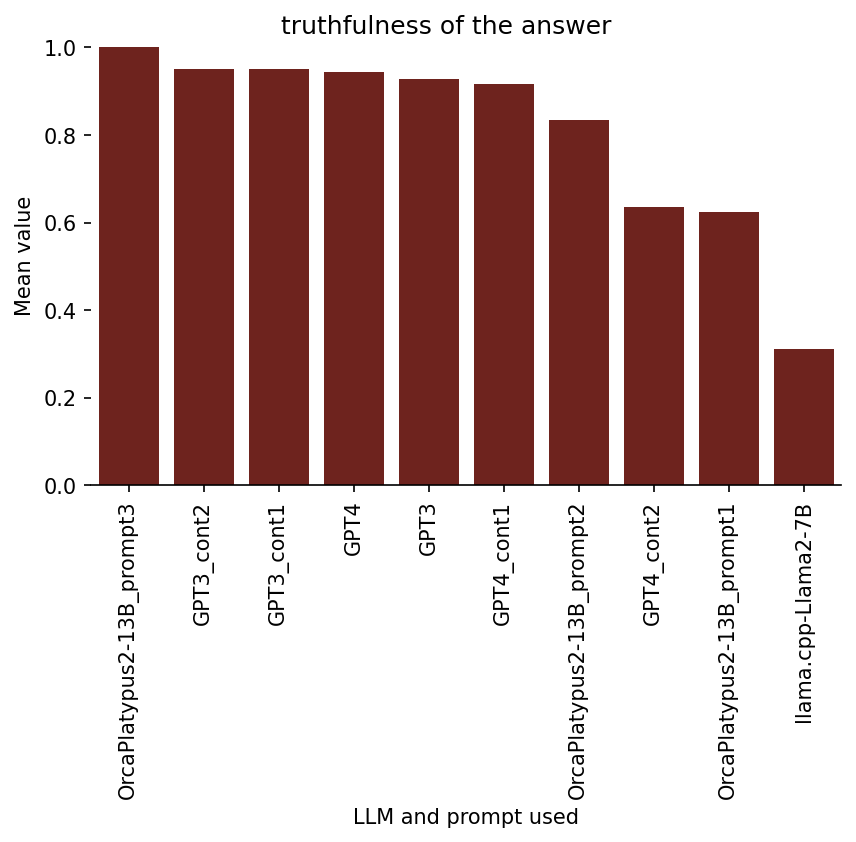

Ratings on 3. Truthfulness

Note that high truthfulness may not necessarily imply high quality of a spaced repetition flashcard, because, for example, the question-answer pair may be far too obvious or far too difficult. Also note that, the truthfulness property isn’t necessarily very important for this task (at least to me), because the AI-augmented spaced repetition card creation process would involve checking and/or adjusting each AI-suggested flashcard before adding it to the deck.

Here is the bar graph of the results:

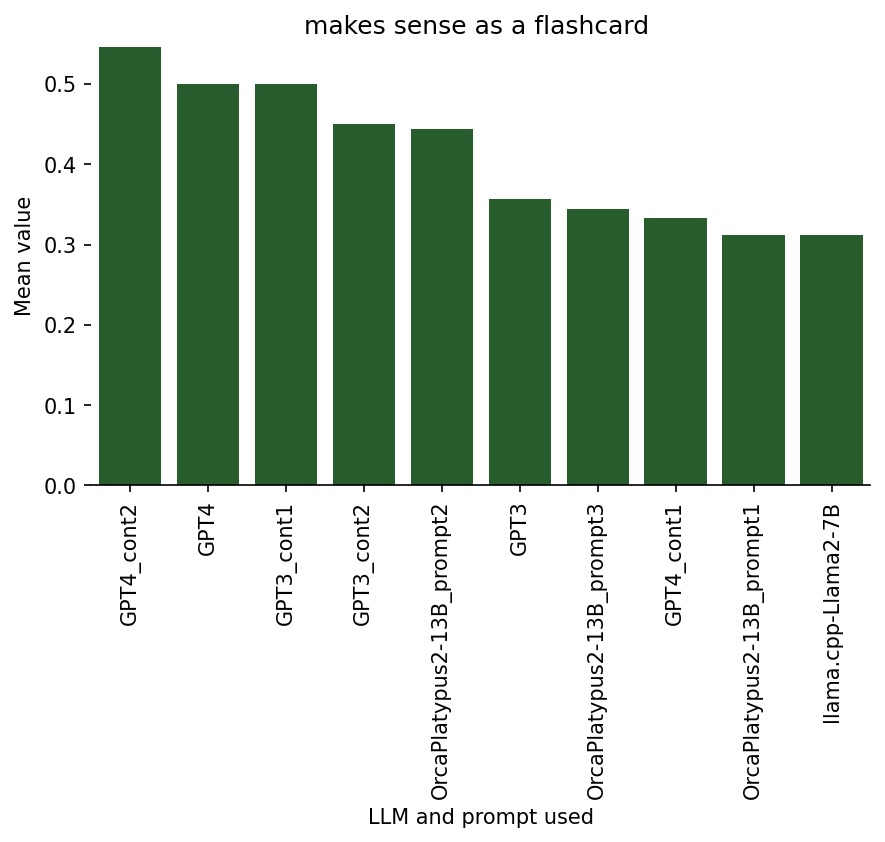

Ratings on 4. Making sense as a flashcard

There is some conceptual similarity between this rating dimension and the one titled “would I use a similar Q-A pair in my deck?” (results below), because both of them can be viewed as measures of overall quality for flashcards. However, the crucial difference between them is that I considered the “would I use” category as something personalized to me, while the ratings in the “makes sense” category are intended to assess whether it could be a good flashcard generally for somebody. That is, I might rate a given flashcard high on the “makes sense” dimension, while the specific question and answer aren’t something that I specifically would want to include in my deck (for example, it could be a great question, but just not on an aspect that I personally find interesting or important to know).

Also, because I actually went through the process of creating new flashcards based on the AI-suggested ones, I can answer the question “am I going to use a similar flashcard?” with far more certainty than the question “does this make sense?”. One can observe this on how the following bar graph differs in range and separation of models/prompts compared to the graph in the next section.

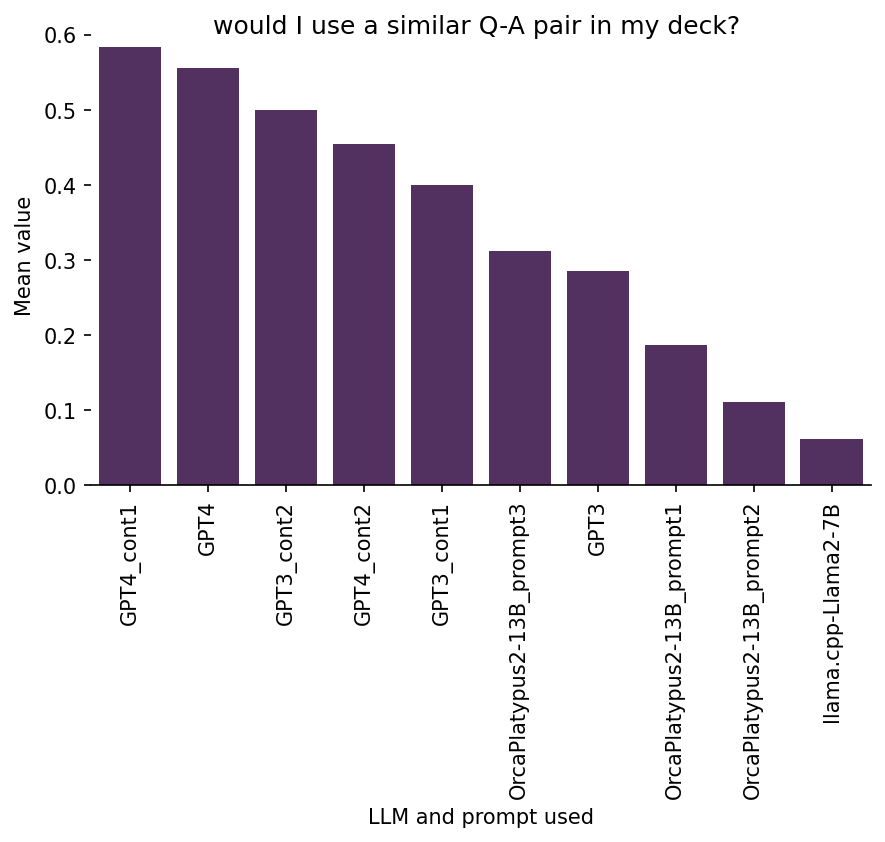

Ratings on 5. Would I likely use a similar flashcard in my Anki deck

I consider this to be the main quality indicator for the generated flashcards, since this entire exercise is about generating cards for my own Anki deck. I also find it to be confirmed as the most suited for a primary metric role, after observing the limitations of the other rating categorizations and the text embedding approach. Moreover, this variable in a way combines all the other rating dimensions I used.

Here is the breakdown of the results:

We see that (somewhat more) manually curating the input to the offline open-source models improved performance substantially (see OrcaPlatypus2-13B_prompt3 vs. the other open-source models). The same is true for several other rating dimensions above. But, as I have mentioned before, this has limited utility, because if I need to manually curate the input text, I could just as well create the flashcards without the help from AI.

Interestingly, I don’t see any particularly strong correlation of the “Would I use a similar flashcard?” ratings with any of the other rating dimensions. This implies that it might depend to a large degree on other not captured factors whether I will use an AI-generated flashcard as basis for creation of new cards for my Anki deck. Perhaps I didn’t capture some other important dimensions of flashcard quality, such as the uniqueness or originality of an AI-generated flashcard, or something else that I didn’t think of. Or it could be just highly personal and strongly depend on my specific background, interests, and taste, which are much harder to quantify or measure.

Takeaways

There is discussion of the result in the individual subsections above, including some concluding remarks, and I don’t want to repeat that information. But here are some key takeaways that I took from the experiments.

- Based on the results above it appears that, as of November 2023, among the compared models, OpenAI’s GPT models are best for generating flashcards on complex topics for spaced repetition systems such as Anki, and they are very inexpensive to use (for creating a few flashcards).

- It is convenient to have the longer context length of GPT-4 Turbo as it allows to feed it more source material.

- While the GPT models handled the raw input of scraped web articles very well, the local models (the ones that would run on my limited hardware) were somewhat challenged by it and improved considerably after the input was manually formatted and more curated, which takes human time.

- So, it appears that the locally run open-source models make limited sense for this task, unless you want to do this really at scale, or if you just like to tinker with these open-source solutions for fun even if they may be slightly inferior. Moreover, it should be possible to tune the models and prompts far beyond what I have tried to improve performance on this task.

On another note, the AI-augmented spaced repetition flashcard generation process strongly encouraged me to have a much deeper look at the topic of Fleiss’ Kappa and similar measures than I would have otherwise. Because some of the suggested flashcards are very interesting, but, at the same time, are missing important context or explanations (or proofs in case of mathematics) which weren’t sufficiently covered/explained in the Wikipedia articles that I fed to the models, it forced me to read (parts of) several academic research papers. So, the AI-augmented process sort of strongly motivates you to look more deeply into the topic by providing short intriguing bits of information as concise question-answer pairs.

While I presented a semi-rigorous comparison along multiple rating dimensions, I may have failed to capture some other important aspects of the quality of AI-generated flashcards. Moreover, some of my assigned ratings could be highly subjective, because there is naturally a considerable level of subjectivity in what constitutes a high-quality flashcard for spaced repetition, depending on personal taste and experience, the topic and one’s prior knowledge of it or around it, various aspects of the context of the spaced repetition practice, etc. Therefore, it would be hard to justify the amount of time and effort needed to improve the prompt, input material, and models to achieve the optimal flashcards for ones exact personal preferences and conditions (which, in addition, will probably vary from one occasion to another or over time). So, overall, it seems that for now it’s probably best to use LLMs only to get some sub-optimal flashcards to use as a starting point for manual editing. Some AI-generated cards may even highlight interesting aspects which the user would have overlooked otherwise.

Advice if you want to do something similar

There are many excellent resources on LLMs to get started – some that have helped me are:

- Jeremy Howard’s video lecture that I already recommended above: A Hackers’ Guide to Large Language Models

- The documentation of the relevant Python packages, such as the OpenAI API python package, tends to be excellent in my experience.

- Andrej Karpathy’s talk Intro to Large Language Models

- A few academic presentations that I attended over the last few months (majority at KDD 2024).

In my case, I basically watched the two videos linked above, and then was able to figure out how to do anything that I wanted to do by just reading the explanations and examples in the docs of the relevant Python packages and of models at Hugginface.

References

- Nielsen, M. (2018). Augmenting Long-term Memory. http://augmentingcognition.com/ltm.html.

- Nielsen, M. (2019). Using spaced repetition systems to see through a piece of mathematics. https://cognitivemedium.com/srs-mathematics.

- Wikipedia. (2023). Fleiss’ kappa — Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Fleiss’%20kappa&oldid=1183551918.

- Wikipedia. (2023). Cohen’s kappa — Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Cohen’s%20kappa&oldid=1188549993.

- Wikipedia. (2023). Scott’s Pi — Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Scott’s%20Pi&oldid=1151174394.

Footnotes:

-

Different model-prompt combinations resulted in different numbers of AI-generated flashcards, but somehow by random luck the total summed to exactly 100. ↩